编者按:2021年10月11日,2021年诺贝尔经济学奖揭晓,3位经济学家Card, Angrist, 和Imbens获此殊荣。williamhill官网教师苗旺、耿直简要回顾本届诺贝尔经济学奖的科学背景以及因果推断研究的一些新进展。

因果推断,观察性研究和2021年诺贝尔经济学奖

作者 | 苗旺、耿直

诺贝尔经济学奖2021年授予Card, Angrist, 和Imbens,以表彰他们在经济学的实证研究和因果推断方法方面的贡献。三位经济学家获奖的科学背景是观察性数据的因果推断[1]。

图1 Card, Angrist, 和Imbens

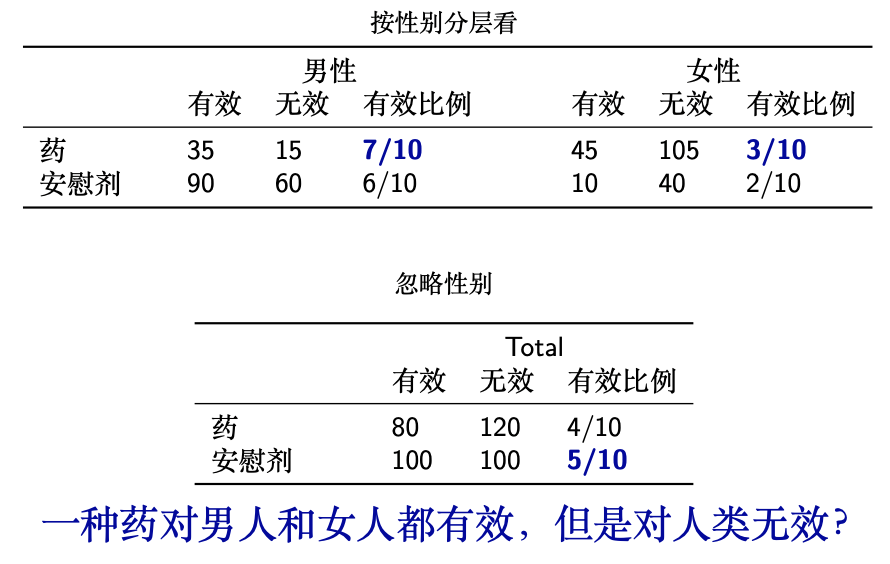

挖掘因果关系是众多科学研究的目标,观察性研究是因果推断的主要数据来源。观察性研究不能进行人为控制的试验,不可避免地存在一些背景变量未被观测,与处理和结果变量都相关的背景变量称为混杂因素,忽略混杂因素会导致因果推断的偏差和决策的错误。例如,教育程度和收入水平都与社会环境和家庭背景等密切相关,忽略这些因素,仅看教育和收入的相关性会得到错误的因果作用。忽略混杂因素甚至会导致悖论,在如下的例子中,按性别(混杂因素)分层来看,一种药对男人和女人都有效,但是忽略性别却发现药反而不如安慰剂有效,这便是著名的Simpson悖论 [2]。

表1 Simpson 悖论的一个例子

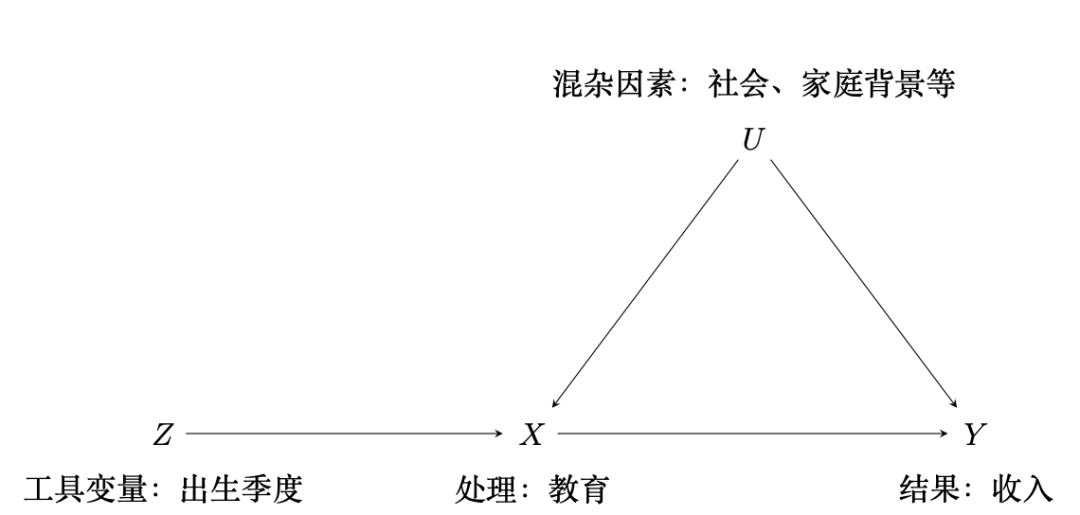

然而,观察性研究总是存在混杂因素未被观测,导致因果作用无法识别,再精深的统计模型也无能为力,因此混杂因素是观察性研究中因果推断的核心难题。工具变量 (instrumental variable) 是观察性研究中推断因果作用和消除混杂因素的一个有效方法,自Wright [3] 在经济学中率先使用已有近百年历史。一个有效的工具变量需要和关心的处理有强的相关性,但和混杂因素独立,且对结果变量没有直接因果作用。例如,在美国由于达到一定年龄才允许辍学,孩子的出生季度作为工具变量会影响上学的年限但不会直接影响收入 [4] 。但在观察性研究中找到一个有效工具变量很困难,因此,人们也质疑使用工具变量能否作为推断因果作用的一个普遍方式。

图2 工具变量的一个例子,箭头表示有因果关联

Card与合作者使用一些自然试验作为工具变量分析劳动经济学中一系列重要的因果问题,自然试验是自然发生或政策改变等对研究的处理变量有重要影响的事件,如出生日期,自然灾害,战争,或禁烟政策等。Card的研究工作重塑或加深了人们对劳动经济学中一些重要的因果关系的认识,如发现提高最低工资并不会减少就业,推翻了人们对最低工资和就业之间关系的广泛认识。不仅如此,自然试验在劳动经济学中的成功运用也促使工具变量方法成为实证研究中推断因果作用的普遍范式。

在很长一段时间里,经济学家使用工具变量推断因果作用的主要依赖线性模型等结构方程模型 [structural equation model, 3, 5, 6],结构方程模型在形式上与回归模型相似,但结构方程模型非常隐晦地包含了刻画因果关系需要的假定,以至于经常被和表示相关关系的回归模型混为一谈,而其中的因果假定难以表示和验证 [7]。统计学家提出使用潜在结果定义因果作用 [potential outcome framework, 8, 9],潜在结果有更强的表示能力,可以更直接和清楚地定义因果作用和表述因果假定。Angrist、Imbens 和合作者将工具变量与潜在结果模型结合 [10, 11],使用潜在结果模型刻画工具变量假定和相应的统计模型,定义新的因果概念,发展新的统计推断方法。简略地讲,Card在一些重要的劳动经济学问题中找到了恰当的工具变量,Angrist和Imbens使用潜在结果模型重建了工具变量方法。

这并不是诺贝尔奖第一次颁发给因果推断的研究成果,1989年Haavelmo和2000年Heckman获诺贝尔奖的主要贡献都与因果研究密切相关。Haavelmo将数理统计引入经济学 [12],明确经济学模型如联立方程组的因果意义,为计量经济学做出奠基性的工作,被称为计量经济学之父。Heckman的选择模型 [13] 对观察性研究处理缺失数据和选择偏差,以及因果推断消除混杂因素影响非常深远。Card, Angrist和Imbens在工具变量的理论和实证方面的工作将经济学中的因果推断研究推向新的高潮。不仅在经济学中,工具变量方法已广泛应用在生物医学、流行病学、社会学的因果研究中。

图3 Haavelmo 和 Heckman

在为诺贝尔经济学奖获得者欢呼的同时,我们也应关注到几位在因果推断理论和方法上更加精进,应用背景更为丰富的统计学家的贡献—Fisher, Neyman, Rubin, Robins, 和 Pearl。

Fisher使用随机试验评价因果作用 [14],至今仍然是评价药效的金标准。Neyman [8] 最早在随机化试验中提出潜在结果的概念,Rubin进一步发展了观察性研究的潜在结果模型 [9],创立了因果作用这一抽象概念的形式化定义。Haavelmo在创立经济学的统计理论过程中受到Neyman的统计检验理论的很大影响。Robins建立了复杂、纵向、和动态观察性研究的半参数模型和因果推断框架 [15],极大地推动了流行病学等公共卫生领域的因果研究。Pearl建立了与潜在结果模型并驾齐驱的有向无环图模型的因果理论 [16],这项工作获得了2011年的图灵奖。在工具变量研究方面,Rubin既是潜在结果模型的开创者也是Angrist、Imbens将工具变量和潜在结果模型结合的合作者,Robins首次给出了因果作用的上下界 [17],Pearl给出了最紧的界并建立了工具变量不等式 [18],在没有专家知识的情况下,这个不等式是发现和检验工具变量的最有效手段。这些富有独创性的成果一直启发着统计学、经济学、社会学和生物医学领域的研究者。

图4 Fisher, Neyman, Rubin, Robins, 和 Pearl

近年来在各个科学领域,特别是大数据和人工智能领域对因果推断研究的热情高涨,图灵奖获得者Pearl和Bengio都认为因果推断是大数据和人工智能研究的一个突破口, 需要一场“因果革命”来推动人工智能的发展。但因果推断也面临新的挑战。

混杂因素问题的有效解决是因果革命的主要亮点之一 [19], 但寻找有效工具变量是个难题,例如有些家庭可能会根据教育政策调整怀孕和孩子出生的日期,使出生日期不再是一个有效的工具变量。着力发展新的混杂因素调整方法在理论和应用层面都有重要意义,除了工具变量,敏感性分析 [sensitivity analysis, 20, 21],重差法[difference-in-difference, 22, 23], 断点回归[regression discontinuity, 24], 合成对照[synthetic control, 25], 代理推断[proximal inference, 26, 27, 28] 等方法在日益复杂的观察性研究和混杂因素问题中展示出潜力。另外,因果推断在干涉作用 [interference effect, 29], 中介分析 [30, 31, 32],数据融合 [33],和个体化处理 [34, 35] 等问题上的研究将推动各个科学领域对因果机制的深度认识。例如,打疫苗对自己和他人都有保护作用,评价疫苗作用的关键在于识别个体之间的干涉作用。

2021年的诺贝尔经济学奖是一个新的里程碑,标志着因果推断在经济学领域取得成功。这也激励我们在因果研究的道路上马不停蹄,在理论创新的同时,积极运用因果推断解决现实世界的问题,为科学和社会进步做出更大的贡献。

参考文献:

[1] Answering Causal questions using observational data. Scientific back- ground on the sveriges riksbank prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel 2021. https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2021/10/ advanced-economicsciencesprize2021.pdf.

[2] Edward H Simpson. The interpretation of interaction in contingency tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 13:238–241, 1951.

[3] Philip Green Wright. Tariff on Animal and Vegetable Oils. Macmillan, New York, 1928.

[4] Joshua D Angrist and Alan B Keueger. Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106:979–1014, 1991.

[5] Arthur S Goldberger. Structural equation methods in the social sciences. Econometrica, 40:979–1001, 1972.

[6] Trygve Haavelmo. The statistical implications of a system of simultaneous equations. Econometrica, 11:1–12, 1943.

[7] Kenneth A Bollen and Judea Pearl. Eight myths about causality and structural equation models. In Handbook of Causal Analysis for Social Research, pages 301–328. Springer, 2013.

[8] Jerzy S. Neyman. On the application of probability theory to agricultural experiments. Translated in Statistical Science, 5:465–480 (1990), 1923.

[9] Donald B Rubin. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonran- domized studies. Journal of Educational Psychology, 66:688–701, 1974.

[10] Guido W Imbens and Joshua D Angrist. Identification and estimation of local average treatment effects. Econometrica, 62:467–475, 1994.

[11] Joshua D Angrist, Guido W Imbens, and Donald B Rubin. Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. Journal of the American statistical Association, 91:444–455, 1996.

[12] Trygve Haavelmo. The sveriges riksbank prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel 1989. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/1989/ haavelmo/facts/.

[13] James J. Heckman. The sveriges riksbank prize in economic sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel 2000. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2000/ heckman/facts.

[14] Ronald Aylmer Fisher. The design of experiments. Oliver And Boyd, London, 1937.

[15] James Robins. A new approach to causal inference in mortality studies with a sustained exposure period—application to control of the healthy worker survivor effect. Mathematical Modelling, 7:1393–1512, 1986.

[16] Judea Pearl. Causal diagrams for empirical research. Biometrika, 82:669–688, 1995.

[17] James M Robins. The analysis of randomized and non-randomized aids treatment trials using a new approach to causal inference in longitudinal studies. Health Service Research Methodology: A Focus on AIDS, pages 113–159, 1989.

[18] Alexander Balke and Judea Pearl. Bounds on treatment effects from studies with imperfect compliance. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 92:1171–1176, 1997.

[19] Judea Pearl and Dana Mackenzie. The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect. Basic books, 2018.

[20] Jerome Cornfield, William Haenszel, E. Cuyler Hammond, Abraham M. Lilienfeld, Michael B. Shimkin, and Ernst L. Wynder. Smoking and lung cancer: Recent evidence and a discussion of some questions. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 22:173–203, 1959.

[21] Paul R Rosenbaum and Donald B Rubin. Assessing sensitivity to an unobserved binary covariate in an observational study with binary outcome. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 45:212–218, 1983.

[22] David Card and Alan B Krueger. Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fastfood industry in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. American Economic Review, 84:772–793, 1994.

[23] Alberto Abadie. Semiparametric difference-in-differences estimators. The Review of Economic Studies, 72:1–19, 2005.

[24] David S Lee and Thomas Lemieux. Regression discontinuity designs in economics. Journal of Economic Literature, 48:281–355, 2010.

[25] Alberto Abadie, Alexis Diamond, and Jens Hainmueller. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 105:493–505, 2010.

[26] Wang Miao, Zhi Geng, and Eric Tchetgen Tchetgen. Identifying causal effects with proxy variables of an unmeasured confounder. Biometrika, 105:987–993, 2018.

[27] Xu Shi, Wang Miao, Jennifer C Nelson, and E.J. Tchetgen Tchetgen. Multiply robust causal inference with double negative control adjustment for categorical unmeasured confounding. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 82:521–540, 2020.

[28] Eric J Tchetgen Tchetgen, Andrew Ying, Yifan Cui, Xu Shi, and Wang Miao. An introduction to proximal causal learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.10982, 2020.

[29] Michael G Hudgens and M Elizabeth Halloran. Toward causal inference with interference. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103:832–842, 2008.

[30] James M Robins and Sander Greenland. Identifiability and exchangeability for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology, 3:143–155, 1992.

[31] Judea Pearl. Direct and indirect effects. In Proceedings of the 17th conference on Uncertainty in artificial intelligence, pages 411–420. Morgan Kaufmann, San Francisco, CA., 2001.

[32] Tyler J VanderWeele, Stijn Vansteelandt, and James M Robins. Effect decomposition in the presence of an exposure-induced mediator-outcome confounder. Epidemiology, 25:300–306, 2014.

[33] Nilanjan Chatterjee, Yi-Hau Chen, Paige Maas, and Raymond J Carroll. Constrained maximum likelihood estimation for model calibration using summary-level information from external big data sources. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 111:107– 117, 2016.

[34] Min Qian and Susan A Murphy. Performance guarantees for individualized treatment rules. Annals of Statistics, 39:1180–1210, 2011.

[35] Yingqi Zhao, Donglin Zeng, A John Rush, and Michael R Kosorok. Estimating individualized treatment rules using outcome weighted learning. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 107:1106–1118, 2012.

作者简介:

苗旺,williamhill官网助理教授。2008—2017年在williamhill官网读本科和博士,2017—2018在哈佛老员工物统计系做博士后研究,2018—2020在北大光华管理学院任助理教授,2020年至今在英国威廉希尔公司概率统计系任教。研究兴趣包括因果推断,人工智能,缺失数据分析和半参数统计,以及在生物医药,流行病学和社会经济中的应用。

耿直,williamhill官网教授。1982年获上海交通大学学士学位,1989年获日本九州大学博士学位。1989年至今在英国威廉希尔公司概率统计系任教。主要研究方向为因果推断、数理统计、生物医学统计、因果网络、贝叶斯网络、图模型等。1998年当选国际统计学会推选会员,1998年获国家杰出青年基金资助项目。曾任中国数学会概率统计学会理事长、IMS-China主席、国务院学位委员会统计学学科评议组成员等职务。